Overwhelmed by Suffering? Here’s How to Act Anyway

Confronted with images of immigrant children in cages, how can we get past overwhelm and work toward a solution?

A few days ago, a Facebook friend of mine posted a video of a Texas detention center housing apprehended migrants at the U.S. border. Inside massive enclosures made of chain-link fencing, children sat shoulder to shoulder, huddled in fear. Many had been torn from loved ones—in April and May, the government separated almost 2,000 children from immigrant parents, most as a result of the Trump administration’s new “zero tolerance” policy regarding unsanctioned border crossings. Then the investigative journalism site ProPublica posted audio from inside an immigrant detention facility. “We have an orchestra here,” one border patrol agent deadpanned, as children wailed for their missing parents.

The firsthand evidence of what was happening horrified me. Yet to my dismay, my brain kept manufacturing reasons not to act. Call my senators? I thought. That won’t do any good. And I’m not sure what else to try. Then there was the all-purpose lament that came back to me like a refrain. Nothing I do is going to change the outcome, so why bother? As I scanned my social media feeds, it was clear I wasn’t the only one feeling jaded and overwhelmed. “I fear that I am not doing enough to turn the tides,” one commenter wrote. “Sickened and feel utterly helpless,” someone else chimed in.

A girl and her father rally for immigration reform in Washington, D.C.

A girl and her father rally for immigration reform in Washington, D.C.Most of us want to believe that when we face character-defining moments, we’re going to rise to the challenge and act decisively to help those in trouble. In everyday life, though, it’s easy to let self-doubts, apathy, and mental clutter muddle our response to the surrounding moral landscape—whether it includes unjust discrimination, corrupt institutional culture, or innocent children detained without their families.

Keeping some psychological distance from current events is prudent: It’s what allows us to go on about our lives when the world seems to be spinning off-axis. Taken too far, though, this self-protective impulse can curdle into inaction—and, eventually, into regret at not having done more. Finding the right balance involves noticing when mental paralysis starts to creep in and working to overcome it. That frees you to take action, however humble, in the face of the problem.

It’s a good thing many of us didn’t listen to the despairing, do-nothing voices in our heads when news broke of how immigrant kids were being treated. The public outcry forced the Trump administration to formally end the policy—though it remains to be seen what the new policy will look like or when children will be reunited with their parents. Still, this victory reminds us of an important lesson: When we do act and speak out, it makes a difference.

What stops us from acting?

Hurl enough weight at a building and it’s likely to topple, no matter how sturdy its structure. Something similar happens in our minds when we’re bombarded with news of problems that seem too big for us to handle. When story after story features human suffering on a large scale, the temptation to shut it all out mounts.

It’s no surprise to Paul Slovic that so many of us feel so overwhelmed in response to the current border crisis. Slovic, a University of Oregon psychologist, has devoted years to studying what motivates people to act in the face of injustice—and, just as importantly, what demotivates them. In a series of canonical studies, Slovic demonstrated that as people were exposed to more and more children in dire straits, they became less and less inclined to help them. Slovic calls this kind of emotional distancing “psychic numbing,” and it discourages us from getting involved in problems that seem too outsized or intimidating. We are more intuitively responsive to stories of individuals in crisis—precisely the kinds of stories that are hard to come by due to limits authorities have placed on detention center access. “There are things officials are doing to reduce the emotional impact,” Slovic says. “They’re basically blocking information that would be emotionally upsetting.”

Our motivation to act also suffers when there’s no straightforward solution in sight. “Psychic numbing works in tandem with this feeling of inefficacy,” Slovic says. Many people are more outraged than numb about what’s happening to families at the border—but are still at a loss for what to do because they feel powerless. That can add up to a lot of wheel-spinning. “Reading and posting on social media and worrying have taken the place of focused action,” says Zeno Franco, a psychologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and chair of the Heroic Imagination Project’s board. “I find myself falling into this trap.”

But it’s not just the scale and complexity of the problem that stifle our compassionate response—it’s also the contradictory stories peppering the news landscape. In response to credible reports of family division, administration defenders shared a dailywire.com article that claimed, “The Media Are Lying About Trump Separating Illegal Immigrant Families.” Despite the untruths in stories like this, they can still dilute people’s resolve. It’s a lot easier to wait and see what happens than to sort facts from fictions and take action based on what you’ve learned.

How to act anyway

A good first step toward meaningful action is to pick apart your mental refrains to see how much truth they actually contain.

“Any time a problem seems really daunting, especially when it’s related to a major policy debate like immigration [that] has all sorts of technical detail, people tend to feel like it’s too big for any one person to make a difference,” says Ari Kohen, a political scientist at the University of Nebraska and the author of Untangling Heroism.

In reality, though, there are plenty of steps you can take that don’t require an expert’s mastery of immigration law or a plum government post. Members of Congress do take note—really!—of how many of their constituents express concern about an issue, so calls to their offices are never wasted, especially if members seem to be on the fence about working toward a solution.

You can also donate to organizations that do have the knowledge and expertise to tackle an issue. For example, RAICES (Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services) is a Texas non-profit that supplies legal assistance to migrant families and tries to reunite parents and children. And depending on your position, you can take part in organized resistance. Several state governments, for instance, have refused to deploy National Guard troops to the border.

Such actions are examples of what Franco and other researchers call “everyday heroism”: accessible selfless deeds that, when repeated and multiplied, can add up to meaningful change. In our highly individualistic society, it’s easy to write off the significance of one phone call, protest, or donation among many, but history testifies again and again to the power of collective action.

“Leadership in these situations is a form of self-discipline,” Franco says, “knowing one’s own weak spots and not allowing those to cause you to tire.” To guard against psychic numbing, he suggests reframing your response to the ongoing pile-up of news. Instead of giving in to the temptation to tune out when you hear yet another devastating story, use each story as motivation, fueling your determination to act.

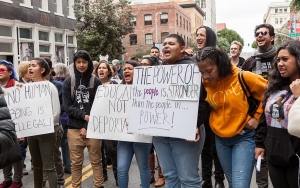

Protesters rally against Immigration and Customs Enforcement in San Francisco this February. © Pax Ahimsa Gethen

Protesters rally against Immigration and Customs Enforcement in San Francisco this February. © Pax Ahimsa GethenAnd while it may not be all that productive to share the same articles and dark memes that are already making the rounds, you can use your social media as a flash point to galvanize others. Try describing what you plan to do to help immigrant families and suggest friends do something similar. That kind of relatable example-setting, studies of moral influence show, is critical to inspiring selfless action, and it matters whether you’ve got 30 followers or 3,000. “The fact you can’t help everyone is irrelevant if you’ve got something you can do,” Slovic says. “Even partial solutions save whole lives.”

Finally, try a time-travel thought experiment. Imagine it’s five years from now and you’re looking back on what happened at the border and how you responded. What action would you be proud of having taken? This might seem like a simple inquiry, but it has value. Multiple studies have found that taking a long “time perspective”—in other words, having a strong sense of how your present actions will shape your future—boosts your motivation and willingness to act.

The Trump administration reversed some of its immigration policies in response to public pressure, but there is no guarantee that the new policies will be implemented—or that divided family members will be reunited or released. That’s why ongoing focused action will be essential. “Your mission for today: To do something with your time so that people in the future don’t say ‘America in 2018’ like we say ‘Germany in the 1930s,’” writer John Scalzi tweeted this week. “Get to it and be glad of the work.”

Follow Us!