THIS MAP SHOWS WHO OWES THE MOST FOR BURNING ALL THAT COAL

A new study bills each American $12,000 for greenhouse gas emissions.

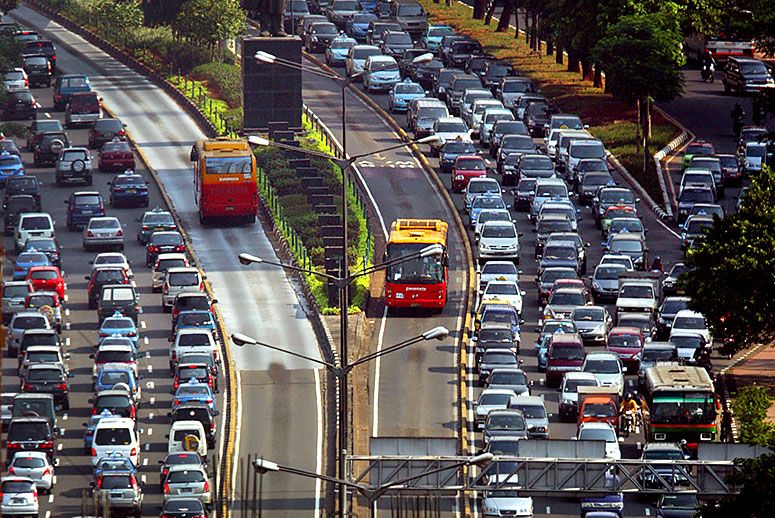

Jakarta, Indonesia. (Photo: Bay Ismoyo/Getty Images)

Sep 10, 2015

Taylor Hill is an associate editor at TakePart covering environment and wildlife.

When it comes to climate change, humans can rightfully claim responsibility for most of the warming the world has seen since the Industrial Revolution.

But should all people be considered equally responsible for the damage done?

Advertisement

Not according to Concordia University researcher Damon Matthews, who calculated which countries contribute the most to climate change and which nations emit the least but nonetheless are paying the price of global warming.

Live in Australia or the United States? You owe $10,000 to $12,000 for your carbon sins. Hail from India or Brazil? You’ve got about $2,000 worth of climate credit coming your way.

So, how did Matthews come up with those figures?

The paper, published in the journal Nature Climate Change this week, looked at the fairest way to determine who should pay to mitigate the impact of global warming. Matthews said one solution is to think of the atmosphere as a finite resource and to label countries as either debtors or creditors based on their contributions to historic greenhouse gas emissions.

Between 1990 and 2013, the U.S., for instance, “over-polluted” by about 100 billion tons when compared with average global C02 emissions. That’s about 300 tons of carbon emissions per person, or the equivalent of making 150 cross-country trips in a family sedan.

Developed nations such as the U.S., Russia, Japan, Germany, and Canada have tallied up the largest carbon debts, thanks to a long history of higher-than-average emissions levels.

Embed This Infographic on Your Site

Carbon debt and credit totals per person are based on the EPA’s estimate of the social cost of carbon dioxide production, which is about $40 per metric ton. Debts and credits are cumulative totals for each country recorded from 1990 to 2013.

On the flip side, developing countries such as India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil, and Bangladesh have racked up carbon credits.

Matthews based his calculations on emissions since 1990 because he wanted to use a time frame in which most of the scientific community and the public had an understanding of humans’ role in climate change.

Advertisement

“Given that ‘responsibility’—at least in legal terms—requires knowledge of the problem, this public awareness is also important to talk about responsibility and potentially culpability for climate damages,” Matthews said.

To obtain a dollar figure for each country, Matthews relied on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s $40-per-ton “social cost” of carbon emissions, which is an estimate of the economic damage from climate change.

“Getting a sense of the scale of global inequalities with respect to historical climate contributions will ultimately lead to a stronger acknowledgement of these issues in international negations,” he said.

Assigning individual debt drives home what’s needed from each country and each citizen to combat global warming, Matthews said.

Embed This Infographic on Your Site

Carbon debt and credit totals per person are based on the EPA’s estimate of the social cost of carbon dioxide production, which is about $40 per metric ton. Debts and credits are cumulative totals for each country recorded from 1990 to 2013.

Since 1990, developed nations have accrued more than 250 billion tons of carbon emissions debt. In other words, they owe $10 trillion to developing countries.

The figure dwarfs the roughly $10 billion in pledges made so far by developed nations to the United Nations’ Green Climate Fund, which seeks to raise $100 billion a year in pledges by 2020 to help developing nations adapt to climate change.

Will Matthews’ debt figure persuade climate negotiators at the Paris climate change talks in December to ante up? Not necessarily, according to Robyn Eckersley, an environmental politics professor at the University of Melbourne.

Advertisement

“Having followed the negotiations for 20 years, I can tell you now the parties will not accept a neat allocation of responsibility based on this kind of metric, although I think this is one of the fairest,” Eckersley told New Scientist.

(Graph: Courtesy Concordia University)

But Matthew believes his carbon debt calculations can help change the conversation around fighting climate change.

“I can’t tell you whether $10 trillion will be enough to finance a global energy transformation to a carbon-free economy while also providing funding to assist vulnerable countries with the cost of climate loss and damages, but it would certainly be an excellent start,” he said.

Follow Us!