NATURE: THE SAVIOR OF CITIES?

In my first year studying for a landscape architecture degree, our textbook for a course on environmental resources was thick, heavy, and weighed down in page upon page of extraneous jargon that obscured the portions that were legitimately interesting and useful. It’s too bad Conservation for Cities: How to Plan & Build Natural Infrastructure, by Robert McDonald, wasn’t around. Even at a quarter the length, it provides exponentially more value – not only for professionals and students in landscape architecture, engineering, planning, and the like, but also city officials, community leaders, and anyone interested in the benefits of integrating natural infrastructure into our cities.

“The twenty-first century will be the fastest period of urban growth in human history,” says McDonald, who is also senior scientist for sustainable land use at the Nature Conservancy. Will this lead to a dystopian end of nature, as predicted by some conservationists? Or will we build cities that exist in co-harmony with nature? “If the city’s plans [to integrate natural infrastructure] are conducted, what is the cumulative effect? What will the city look like? What will it feel like to live in this greener, more resilient city?”

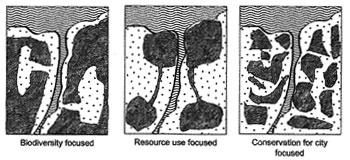

While these are some questions we can only fully answer in the future, McDonald gives us a practical manual for getting there. McDonald’s approach – using conservation for cities – is the product of a framework rooted in the concept of ecosystem services, the many benefits nature can provide us. This is in contrast to conservation in cities, which refers to protecting biodiversity in areas or urban growth; and conservation by cities, the act of making cities more efficient in resource-use and expenditure. Conservation for cities “aims to figure out how to use nature to make the lives of those in cities better. Rather than focusing on how to protect nature from cities, this book is about how to protect nature for cities.”

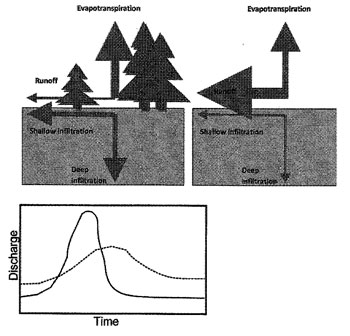

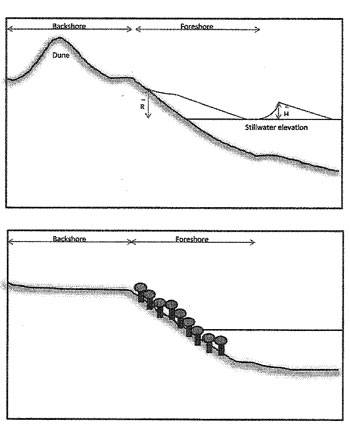

City leaders make decisions based on qualitative and quantitative assessments and then implement strategies, which then must be tracked for success or failure. McDonald spends the core of the book going over mapping, valuation, assessment, implementation, and monitoring methods for ten key areas of ecosystem benefits, each with its own chapter: drinking water protection; stormwater; floodwater; coastal protection; shade; air purification; aesthetic value; recreation value and physical health; parks and mental health; and the value of biodiversity in cities.

When possible, McDonald refers to specific formulas, models, software, and other tools that have proven the most successful. For the more casual reader, these technical details are easy to skim. For the professional looking for practical approaches, these details will likely be useful. It’s also worth noting here that the graphics in this pre-publication proof are somewhat sparse, and tend towards the schematic. Additional footnotes, photographs, and illustrations may be included in the finished book.

Despite the proficient use of market valuation processes, economic indicators, and the like for assessing ecosystem services, McDonald also understands that the value of nature is simply beyond human measures. While professionals and advocates for natural infrastructure are also likely to appreciate the inherent value of nature, that value is difficult to use as an argument against grey infrastructure approaches. Value is calculated in fairly strict black and white economic terms these days.

McDonald uses the “dry and academic” term ecosystem services “because it is standard in the field now, and it makes clear the economic value of nature’s benefits. But [he hopes that] the reader haven’t lost sight of the fact that always behind ecosystem services are people’s lives.”

It’s McDonald’s hope that “rather than completely bending nature to our will, we could bend our will to match nature’s pathways, at least a little bit. The science of ecosystem services gives us some of the crucial tools to follow these other pathways, if we have the love to follow them.”

For those who feel the love, Conservation for Cities offers a compelling trail head to these pathways of the future. I kept thinking I might use that old environmental resources textbook as a resource one day. This year, I finally donated it to make room on the shelf for other books. Conservation for Cities, however, is likely to stay there for quite some time.

Yoshi Silverstein, Associate ASLA, is the founder of Mitsui Design and director of the Jewish outdoor, food, and environmental education fellowship at Hazon, the country’s leading Jewish environmental organization.

Follow Us!